Making vs Maintaining

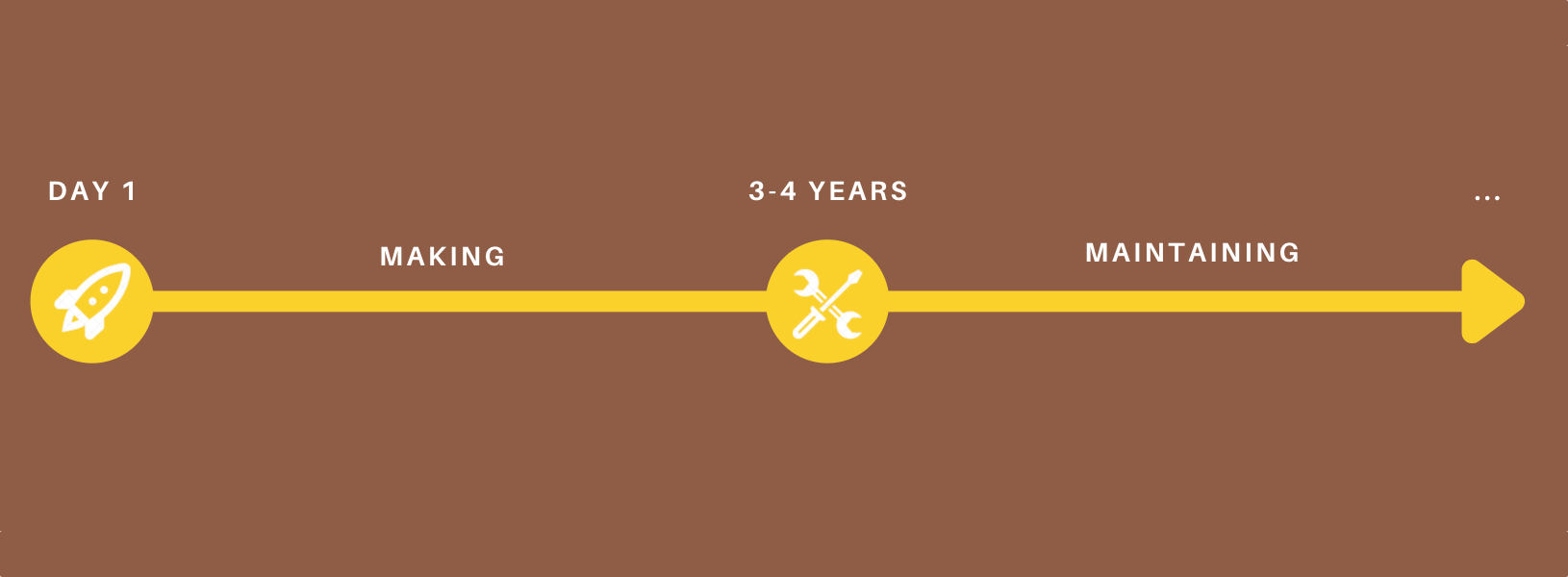

I'm convinced that there are two phases of software development: making and maintaining. An application starts out in the making phase, and then after some period of time, slowly shifts to the maintaining phase. In my experience, this transition happens around 3-4 years after an application is launched.

I call these phases, rather than types of work, because I'm not talking about the difference between bug fixing and adding features (an application will have both new features and bug fixes whether it's been around 30 days or 30 years). Rather, the maintaining phase is when an application gets heavy enough that you can see the results of past decisions. Decisions about what framework to choose, how to structure your database, where and what type of caching to do, patterns to use in your models, all of these decisions add up to a certain heaviness that is just not visible when an application is only a couple years old.

Developers working at contract firms or small startups are often perpetually in the making phase. You're on a new project every 12-18 months, and every project uses the newest JS and CSS framework, and each one has a slightly better approach to organizing controllers, views, models, and business logic. We're all constantly learning, and because you have fresh in your mind a list of the pain points and the positives from your last project, you can roll that experience into your next project.

Unfortunately, the only pain points and positives you learn are the ones from the making phase. The team you leave behind to maintain the application you've built (perhaps for another decade!) will be the ones who experience the impacts of your decisions in the maintaining phase. Patterns that felt a little heavy to you might end up being huge blessings for long-term, big-team maintenance down the road. Patterns that felt perfect to you might end up collapsing under the weight of years of new business requirements and be a source of unexpected pain to the maintainers. These lessons are incredibly valuable if your goal is to build long-lasting, maintainable applications, but people building new applications often don't have access to these lessons.

Conventional wisdom for developers in tech hubs like San Francisco or Seattle is that if you're at a job longer than 4 years, you are leaving money on the table. If you land on teams building shiny new apps every time you join a company, that means you'll be leaving the company just as the application you built is beginning to enter its maintaining phase. You could very easily spend 25 years in tech and never work on an application in the maintaining phase.

A side effect of this imbalance is that developers who are perpetually making may be totally unprepared for the different, unique challenges of maintaining. The first time you encounter an application in this phase, your first instinct will be to rewrite it! "It's just too big, and clunky, and look at all these coding patterns I would never use today -- the only real path forward here is to start from scratch. Oh, and I know just the framework to use for the new app, it came out last month." Falling back to the familiar challenge of making will look more appealing than flexing the unfamiliar muscle of maintaining, even if what you're suggesting would cost the company thousands of hours of labor that probably isn't necessary.

Please don't think I'm suggesting that there's no such thing as a badly-designed application -- that does happen, of course. In some cases rewriting some or all of a codebase may become necessary. The issue is that developers that have spent their entire careers making don't have the experience to tell the difference between a paint point caused by bad overall design, and a pain point that is inevitable once an application reaches a certain heaviness.

The next time you're tempted to rewrite an application, ask yourself what phase the application is in, what pain points you think you see, and whether the rewrite you propose would encounter those pain points again five years from now. Better yet, if you do get an opportunity in your career to work on an established application, take it -- you won't learn the framework that came out last month, but you may acquire an entirely new set of tools and perspectives.

- Previous: Scaling a pixel art game for the browser

- Next: Line \ Continuation